In 1980 the French intellectual

Michel de Certeau wrote about what it was like to look down on the streets of

Manhattan from the 110th floor of the World Trade Center. De Certeau died before

those towers took on the meanings that they have had since 9/11, 2001. But his

point wasn't about those towers in particular. He thought that the “pleasure”

of looking down on the world from a great height was due to the way that it

freed you from the pulsating and ultimately unknowable hubbub taking place at

ground level. The view from above was the God-like perspective which rendered

the world readable at the cost of our separation from it. Cartographers, city

planners, bureaucrats, and administrators viewed the world in this way because

it abstracted populations and landmasses so as to render them knowable,

manageable, and malleable.

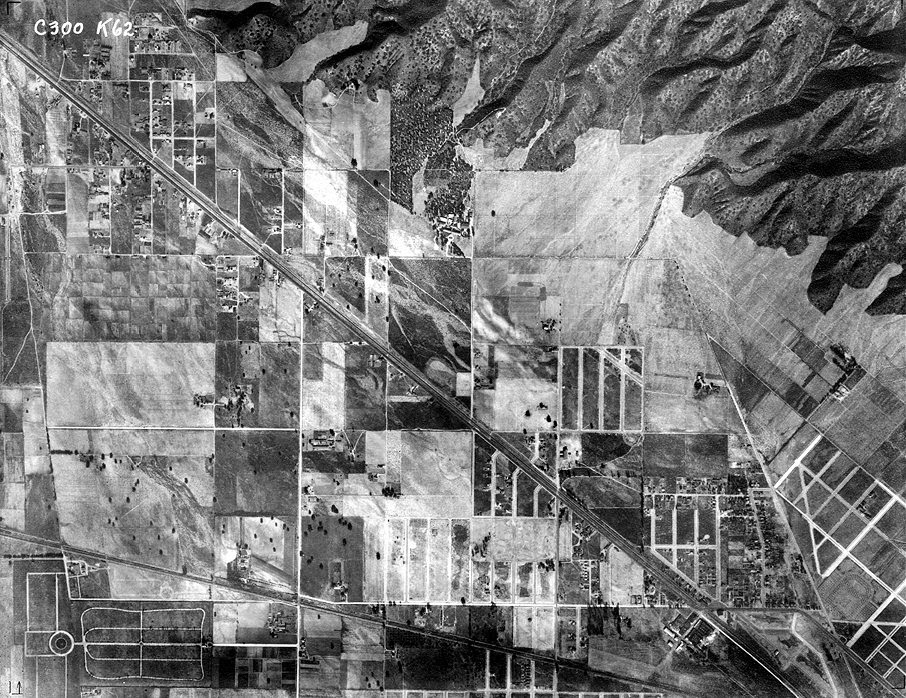

There is pleasure in aerial

photography and it’s hard not to see this as connected to its power to

abstract. Aerial photographs have a special kind of beauty because they both

register the world and offer us a view of that world that most of the time is

unavailable to us. We find it hard to connect the photographs to a world that

we know: much easier to enjoy the patchwork, the shapes, the lines cut by

rivers or roads. That this perspective has been associated with death, with

killing is of course unavoidable. The Orson Wells character in The Third Man justifies his racketeering

in dodgy pharmaceuticals with the view from the top of a Ferris-Wheel in Vienna. “Look down

there” he says “Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped

moving for ever? If I said you can have twenty thousand pounds for every dot

that stops, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money - or would you

calculate how many dots you could afford to spare?”

In a book of aerial photography

that was published in 1953 (Our World

from the Air: An International Survey of Man and his Environment) a

foreword claims that the twentieth century is the century of the air in the

same way that the 19th century was the century of the railway. Because the echo

of the Second World War was still reverberating loudly it at once recognises

that mechanical flight had allowed humans to drop thousands and thousands of bombs

on each other, but wanted to push the reader into thinking about how aerial

photography could be used by “the geologist, the archaeologist, the

town-planner, the sociologist”.

Today when so many more people

have had the experience of mechanical flight, aerial photography still offers

an uncanny vision of the world. The view of the world you get from your budget

airline passenger seat is never really vertical (unless something has seriously

gone wrong) and is always mediated by the slightly cloudy double-glazing of the

tiny windows. Aerial photographs have a calmness that is never available in the

cramped seating of economy class.

They seems to speak more readily

of some of the experiences of the young flyers who became pilots during the

Second World War:

The physically amazing thing

about flying, after the speed impression of taking off and low flying, is that

as you gain height the sense of motion drops away. It’s nothing like looking

out of the railway carriage and seeing the blurry silver worms zipping past or

the ritual nodding of telegraph lines. It is impressively stable and still up there

and this is the important point, the world is laid out for you in unfamiliar

terms… the visual field is flattened more after the plan view of the microscope

section than the elevation that everyday seeing is accustomed to.

This is the artist Nigel Henderson remembering his

experience of flying. It was an experience that went from enormous pleasure to

nerve-wracking fear. However familiar it may become, and however it is used for

instrumental ends, the view from above is also always vertiginous and discombobulating.

A god-like view is the view of someone who has no place. The view from above is

also the view of someone falling to earth.

.jpg)